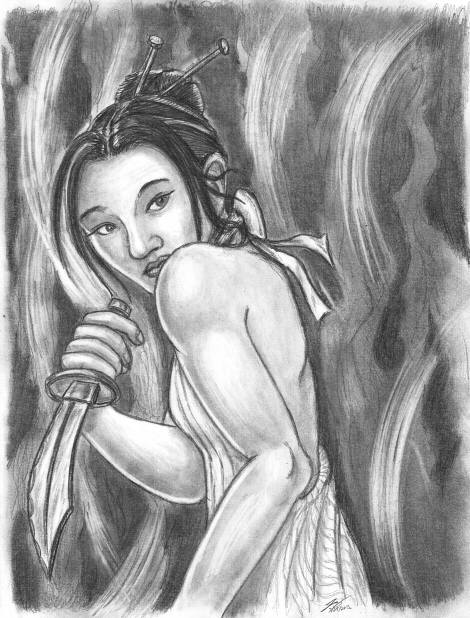

Betrayal II: Nightmare I didn’t set out to do a successor to Betrayal, one of the earliest Dark Side renders done at least ten years prior to this writing. All I knew going into this drawing was that I wanted a figure looking over her shoulder, and that was it. Everything else I invented as it came up. In fact, the similarities between the two drawings didn’t even occur to me until after I’d scanned it and was considering the file name. Like the first Betrayal (and much of my early Dark Side stuff), this was drawn without a reference which presents a plethora of problems that only vast experience drawing from sources can solve. So, not surprisingly, given how much I’ve drawn from real life and photos in the last three years, Betrayal II is worlds improved from Betrayal I. However, I don’t want to pat myself on the back and go into a detailed comparison because, quite frankly, it’s been over ten years. It damn well better be worlds improved. Instead, I’d like to reflect on some of the challenges presented by drawing sans reference. 1.) With a source, you simply have to draw what you see. Without a source, though, an artist has to figure out what is and is not visible purely through imagination which is far more difficult than many people realize because the physical world can be broken down to 100% math and logic, and math/logic are not the friends of the human mind. People operate on persuasion. Tone. Energy. History is full of mobs taking stupid actions because a charismatic leader manipulates their emotions. So, if people can convince themselves of falsities with irrefutable proof staring them in the face, it’s almost impossible not to trick yourself in the abstract realm of pure imagination. Only the discipline of experience can overcome it. Whenever I tackle dynamic poses/angles, in some ways it feels more like sculpting than drawing in that my initial lines tend to go too far out, and as I work on the render I bring them in ... then bring them in some more ... then bring them in yet some more ... almost as if I’m chipping and sanding away at a block of marble, slowly working it into the desired shape. In this particular drawing, I kept refining and re-refining her shoulder blade and the arc of her back because the original lines made her look unusually thick (kinda like a D&D dwarf who have the proportions of a brick). And maybe it’s still a little wrong, but I think the final result looks pretty good. 2.) With all the thought going into the slew of decisions that accompany every render (lighting, value range, textures, rendering techniques, line qualities, etc) not to mention the careful calculations to figure out perspective, visibility, anatomical details, it’s very easy to make logistical mistakes that require a completely different train of thought—stuff that may not be obvious at a glance. For example, I looked at my hand long and hard trying to figure out how she would grip the knife, what would be hidden, and how light would play off each of her digits. I think I did a pretty good job there. I even thought about which direction the blade’s edge should face, but I didn’t think it through enough. Go pick up a knife. You’ll hold it so the blade is parallel with your arm. This is because any meaningful cutting motion comes from your elbow, not the wrist—a fundamental tidbit on human physiology that’s not immediately obvious in a still image. Here, I’ve drawn the blade perpendicular to the arm meaning she’d have to perform a backhanded slap to slice anyone which would feel prohibitively awkward. Go ahead, try it (preferably with a butter knife when no one is around). She could still stab with it, but that’s about it. Like I said, drawing it you’re generally concerned with how it looks in still frame which is a different train of thought than the mechanics of functionality and efficiency. The more experience you gain as an artist, the less you have to consciously think about proportions, perspective, and lighting because it becomes natural allowing you to think about these sorts of things. 3.) Genericness. The human brain has an amazing capacity to ignore 90+% of the information it takes in, lumping everything together into as few broad categories as possible. We see a house, and we don’t pay attention to the doors, the bricks, the windows, the shutters, the roof, or anything. We just think “house.” Thus it should come as no surprise that when people draw from imagination their renders tend to look bland and unremarkable. Artists, though, when drawing from sources have to train themselves to go against their brain’s modus operandi to start noticing these details everyone else ignores, and when they draw from imagination (hopefully) those details will remain resident in their memory to inspire touches of specificity. And I think here there’s actually an interesting comparison between Betrayal I and Betrayal II. Even back then I was aware of the genericness factor, so I took the kitchen sink approach whenever I had to design anything which explains why so many of those early drawings are overly complicated. So, yes, with the first Betrayal, there’s more going on with her hair, her outfit, and her dagger, but one thing the last few years has taught me is the difference between generic and simple.

—Jay Wilson Also available: the first Betrayal |

|

|