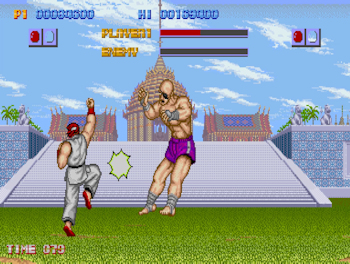

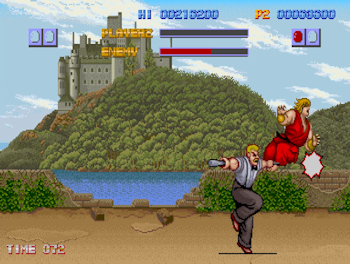

By the time I got around to capturing this frame, I was so fed up with Street Fighter's controls that I was literally just mashing buttons while performing quarter circle motions.

Most fighting games give a point to both sides in the event of a double K.O. In Street Fighter, however, it goes to nobody, meaning you have to endure at least two more rounds to take the match.

The CPU opponents basically have just one move that they spam nonstop, which is impossible to deal with given the lack of animation, reaction time, and laggy controls.

Review by Jay Wilson In the 90s, I played various editions of Street Fighter II, both legitimate and bootleg, in arcades, bowling alleys, and even convenience stores. At home, my SNES copies of World Warrior and Hyper Fighting sat next to each other while I played a rental of New Challengers. And while in this literal sea of Street Fighter II’s, I recall reading a letter in Electronic Gaming Monthly asking about the elusive first entry that didn’t seem to exist, not in the United States anyway. To my surprise, EGM responded that Street Fighter 1 had, indeed, been developed and was, indeed, released—yes, even in our hemisphere. But where was it? And how come no one seemed to know anything about it? Then lo and behold, one day while visiting a distant arcade, I encountered the mysterious curiosity that was the original Street Fighter. I put a couple quarters in and quickly confirmed everything I had read: it doesn’t just suck, it’s completely unplayable. But, why is it unplayable? Well, the lore tells us that in 1987 the hardware was not up to the challenge, and while I certainly believe that crippling ROM constraints contributed to the inadequate animation, part of me wonders ... Street Fighter had two versions: one featuring the standard six button layout the series is known for pioneering and the other featuring two pressure sensitive pads that determined punch/kick strength by how hard you hit it. But let’s come back to that in a minute. Street Fighter seems to vaguely, if not randomly, respond to your inputs. Push a punch button, and it might not come out. Even if it does, it won’t come out when you want it to. Try and throw a fireball? Good luck. This alone breaks the game because the key to gameplay is interaction, but if interaction is unreliable, what’s the point? Everyone who’s played a platformer has had that “I pushed jump!” moment. You know, when you race towards a ledge full speed to make a tricky long distance leap, you push the button at the last possible second, and your in-game avatar runs right off the edge and dies as you spring out of your seat screaming, “I pushed jump, damn it!” Yeah, that moment. That’s the entirety of Street Fighter 1. “I pushed punch!” “Where’s my hurricane kick?!” “I shot a fireball!!!” “Why can’t I do a dragon punch?!?!” “Jesus Christ, let me do something! ANYTHING!!!!!” But believe it or not, SF1’s controls are more consistent than people give them credit for—they have to be; it’s a computer program. However, just because something is consistent on a code level doesn’t make it consistent on a human level. Expectation plays a key role. Most people understandably expect a punch to come out when a punch button is pressed. That does not happen. You see, Street Fighter 1 only registers said punch upon the button’s release. Press punch and hold it, Ryu will do nothing. Continue holding it, and Ryu will continue to do nothing. Let the punch button go, and Ryu will finally throw a punch. But if you hold the punch button too long, Ryu is back to doing nothing. Now, this is not a defense. While defying expectations can sometimes be a good thing, sometimes even profoundly changing how we think about a subject, the overwhelming majority of the time it’s just bad design. And this is definitely just bad design. Even if you adjust your playstyle to get away from these pre-formed, biased, “human” expectations to objectively match how the machine actually behaves, it does not make Street Fighter any more playable even if you are able to throw fireballs consistently against a dummy player who just stands there because the counterintuitive controls are only the beginning of Street Fighter 1’s problems, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

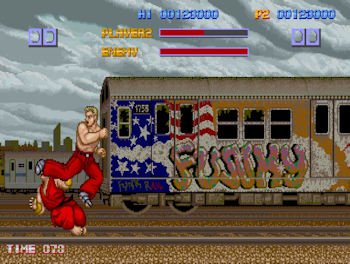

I make it a policy to make the subject of a review look its best with the screen captures. But I encountered way too many glitches like this to not call attention to it.

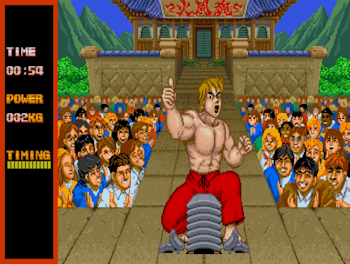

After every couple of matches you play a bonus stage that involves breaking blocks or boards.

Notice the lifebars are not mirrored and do not feature the characters' names, rather are stacked and labelled generically as “Player” and “Enemy.”

You'll hear this quote a lot with Street Fighter's infamous, barely intelligible speech. The enemy portrait might be different, but the post-match dialog is always the same.

Back to the “deluxe” pressure plate controls: if the intensity used to strike the plates determines light, medium, and heavy attack, if it has to take a measurement and perform a calculation before sending the signal on, doesn’t that explain the delayed input? Especially considering minimalist programming to accommodate limited ROM capacity in the 80s? And how much coding difference is there between six-button and pressure plate versions of Street Fighter? Is it enough to optimize and take full advantage of the six button layout, or did Capcom recycle the pressure plate code with a digital band-aid—just enough to get it “working”? Hold on to that thought. Another quirk of Street Fighter’s controls: if you hold fierce punch down, then medium and light punches will no longer register at all. Same thing with kicks. Hold light kick down, then mash medium and a hard kick. Ryu will stand there and do nothing. Let go of light kick, and Ryu will finally lash out with his leg. Now, you can use kicks while holding down a punch and vice versa, but one punch locks out all other punches, and one kick locks out all other kicks. So here’s a question: if the machine is using one pressure plate for punch and one pressure plate for kick, doesn’t that explain why you’re limited to only one punch and one kick at a time? If the six button version uses the same code with a digital band-aid, doesn’t that explain why it suffers from the same limitation as the pressure plate version despite not having the same physical restriction? This is purely conjecture and may not factor into the equation at all, but like I said, part of me wonders how much hardware shortcomings truly contributed to Street Fighter 1’s unplayability and how much of it is because they pursued a silly gimmick. The other glaring problem is the lack of inbetween frames. In animation, there’s something called key frames which are the most prominent poses of an action. A walk cycle, for example, would have a character’s right foot fully extended as one key frame, and the next key frame would have that same character’s left foot fully extended as he takes the next step, and so on for each successive step. Later on, inbetween frames are added to smooth out the walk and make it appear fluid and seamless. Key frames are rendered first as a kind of rough preview of the overall sequence because ten key frames are easier to fix than two-hundred and forty. Street Fighter basically has no inbetween frames. So, for a punch, Ryu goes from his neutral stance, to fist fully extended, and back to neutral stance. That might not sound so bad until you see it in motion and have to react to it, deciding whether to guard high or guard low. For some characters, something as simple as moving forward and backwards is a spastic, jittery mess. The problem is only compounded with the more complex maneuvers like Gen’s windmill-like arm-strikes or Adon’s front-flipping jaguar kick. These attacks look like the individual slides of a power point presentation, clicked through as fast possible. And because the range of motion is so great, each frame does not seem like a continuation of the one before it, breaking down the cohesion that creates the illusion of one continuous motion. Now your mind is trying to process a series of seemingly random, disjointed poses at breakneck speed which is especially bad because the damage in Street Fighter is off the charts. I’ve outright killed with a single dragon punch. You would think that would render the game mind-numbingly easy. But oh no. That damage can be reciprocated. Later enemies kill you with an average of about three hits—not combos—three individual hits. Sagat’s tiger shot takes off a minimum of 75% of your health. And don’t forget: all of your attacks have a delay (if they come out at all) while these enemies are teleporting over, hitting you a few times, and killing you in the blink of an eye. Bam! Bam! Bam! Dead. There will be rounds—many, many rounds—where there is nothing you can do. Literally nothing. The CPU will win. And keep in mind this is coming from an obnoxious little prick who would go into stores that had demos of Street Fighter II Turbo, who would put in the hyper code, and play at the fastest speed using Zangief to troll the other kids who did not own the game and who just wanted to play something while their parents shopped. I trained myself on my own copy to play the most complex character at the most unreactable speed ... and even with that under my belt—even when I adjust my game, knowing that the buttons register only upon release—I still can’t keep up with Street Fighter 1. Not when the CPU opponents go into their epileptic, flickering rush-down of two-hit death.

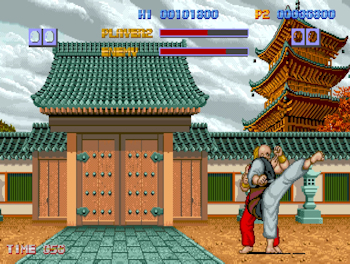

I wanted to show a picture of Gen because he returns in the Alpha series; I also wanted to genuinely compliment the backrounds because they are the best aspect of the game ... and, of course, Gen's stage is the blandest.

Adon's jaguar kick has only three frames of animation.

For perspective: Street Fighter II’s characters have about twice as many frames just standing idle. You see, animation not only provides visual cues for you to recognize as well as also providing a window of opportunity to react, but more importantly, it simplifies hundreds of individual frames into a single, easy to follow movement. Even if the animation plays at a ridiculous speed, your mind will still be able to follow it because it’s not 50,000 individual images; it’s one dragon punch, one fireball, and one hurricane kick. Because you can follow it, you can remember it, and that memory will allow you to replace reaction with anticipation. Anticipation is what let Street Fighter II remain playable even when it went Turbo ... twice. By far the most interesting aspect of Street Fighter 1 has nothing to do with the game, itself. Rather, Street Fighter II (and the legacy that rose up around it) gives the original Street Fighter its life, dare I say its immortality. The evolution of something so excellent from origins so terrible and the juxtaposition of the two is both instructive and fascinating because Street Fighter II preserved more from its predecessor than one might think. For example, the term negative edge describes the fatal flaw of Street Fighter’s gameplay (ie, the buttons register upon release), but it was not coined until much later when The World Warrior used this very same concept to benefit the players. How could something so crippling in the original facilitate gameplay in the sequel? Because when performing special moves—not normal moves, but special moves—in Street Fighter II, the button counts twice, first when you push it and then a second time when you release it, effectively doubling your chances to time it correctly. And when you figure in pianoing, a technique where you individually tap all three punches (or kicks) in quick succession, you can get up to six chances (three upon the initial press and three more upon release) to nail the input window when your opponent is on you and you’re panicking because you only have a sliver of health and you really, really need that wakeup dragon punch. It makes Street Fighter II consistent not just on a code level, but on a human level. And that is one of the reasons why Street Fighter II is the landmark title that it is, meanwhile the original Street Fighter remains that mysterious curiosity lurking in the shadow of its sequel. It’s kinda funny when you think about it: if it weren’t for Street Fighter 1, we would not have Street Fighter II. And if it weren’t for Street Fighter II, we would not even remember Street Fighter 1. | ||||||||||||||||||||

If a special moves hits just right, it can deal 100% damage such as Ken's dragon punch here.

Sometimes the fireball hits, sometimes the tiger knee neutralizes it, and sometimes the game just doesn't give a shit. | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||