Developed by the French Studio, Dontnod Entertainment, I think there’s some translation issues as to whether Blackwell Academy is a high school, college, or some private school hybrid.

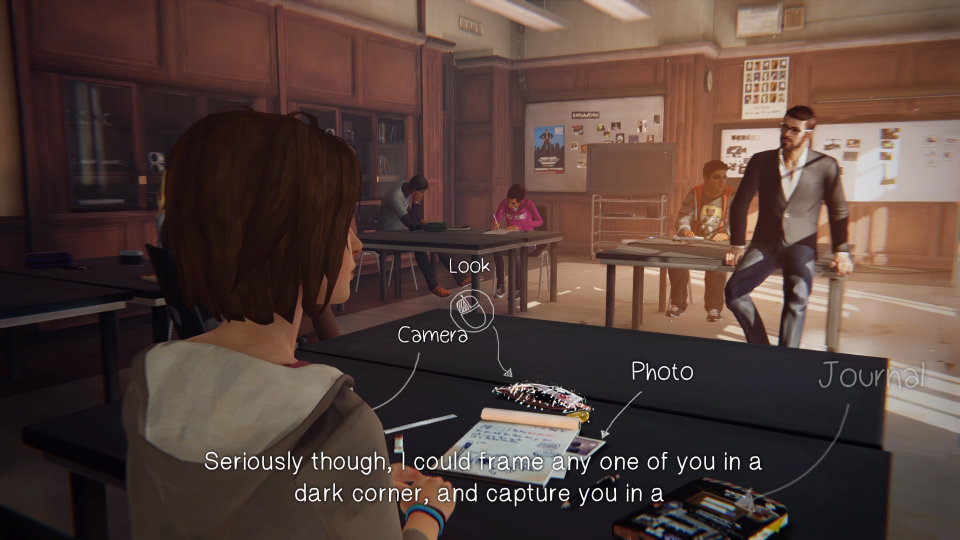

I like how Life is Strange will occassionally let Max interact with her surroundings in real time during natural pauses like while sitting in class during a lecture or waiting for her meal at a diner.

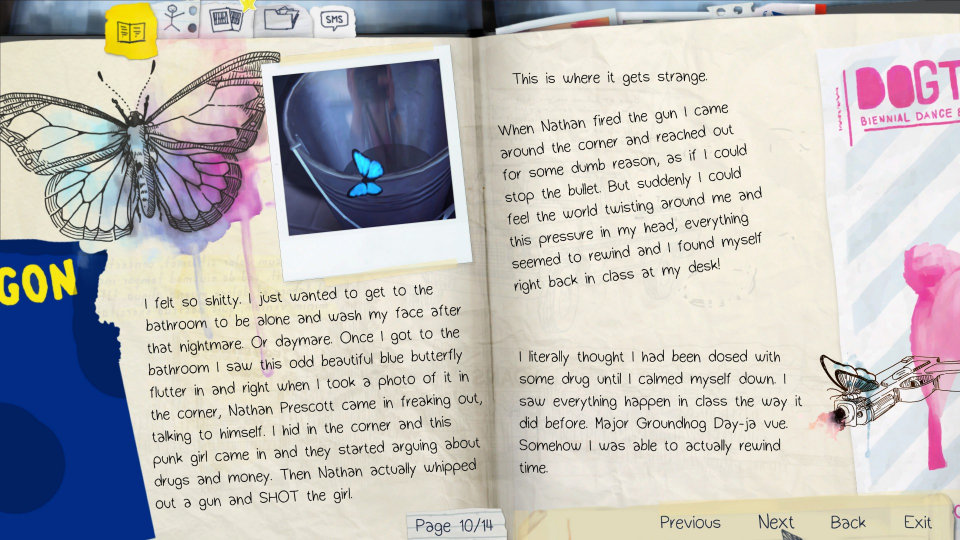

The narrative never explains how or why Max can rewind time. Instead it takes the Twilight Zone route and just focuses exclusively on the human relationships and the emotional impacts of both an original set of events and their timeline-altered variations.

Review by Jay Wilson The interesting thing about Life is Strange is that its signature mechanic, the ability to rewind time, speaking strictly in gameplay terms, is its weakest aspect as it essentially amounts to watching the same cutscene again after a quick-load (albeit, with the possibility of new options opening up.) How the narrative uses this mechanic, however, and the journey it sends protagonist Maxine “Max” Caulfield on is nothing short of magical. You control a meek little metaphorical mouse who is content to take pictures in her own little corner of Arcadia Bay on her path to becoming a professional photographer. She has returned to her home town after a five-year absence, and despite being back for a few weeks, Max still hasn’t contacted her childhood friend, Chloe Price. She makes the excuse that she wants to settle in before getting in touch, but she’s really putting it off because she’s nervous. When her family moved away, she failed to write or call even a single time and has no real excuse. But this failing is so natural, so understandable, so common, that we instantly empathize with Max because it doesn’t make her a bad person; rather, it makes her human. We’ve all lost contact with someone we once loved, not because we put up a wall or walked away; rather, because we just didn’t act. Life has a habit of getting in the way, absorbing all our attention, and sweeping good intentions into the realm of apathy. It’s one of the reasons all of us wish we could turn back the clock and try again. To find time we don’t have. But Max proves she possesses a curious and compassionate heart, which manifests directly in her interactions with her new friends. She’s genuinely hurt when the sweet and innocent church girl, Kate, seems depressed, and Max tries to walk that perilous tight rope of helping her open up without pushing her to. She feels bad when Dana snaps at her for noticing a pregnancy test even though it’s in plain view for anyone to see, and Max considers rewinding time to deliberately ignore it just to protect her friend’s feelings. And as for the stuck-up bitch, Victoria Chase, Max makes a point of stating she admires the photography and artistic talents of the mean-spirited rich girl, more lamenting Victoria’s attitude than condemning her, directing her hatred to the machinations of a clique more so than the human members of it. And across this first chapter it becomes apparent that if there’s good there, however minute, Max Caulfield will at least find it. Whether she holds on to that good or drops nuclear truth bombs, however, that’s entirely up to the player. And while I love how Max starts out, I adore what she becomes. The lost and confused girl paralyzed by terror in a critical moment transforms into a woman so determined to save the people she cares about that when her power starts to come at a physical cost—perhaps even killing her—she doesn’t back away. She doubles down and stops time entirely because Max knows she is the only one who can help; she’s the only one who can save her friend. And I’ve never been so immersed in a game world, so emotionally invested in a character’s fate, as I was when Max pushed through the time-frozen figures to rescue her classmate from self-destruction. I wanted to help her too. And when Max’s power abandoned her, leaving her with only one shot to make things right, I was right there beside her, holding my breath with every mouse click and praying I’d collected enough information to talk her down. And I remember sighing with euphoric relief and feeling an unparallel sense of triumph when the bullied girl reached out to take Max’s hand, stepping away from the brink.

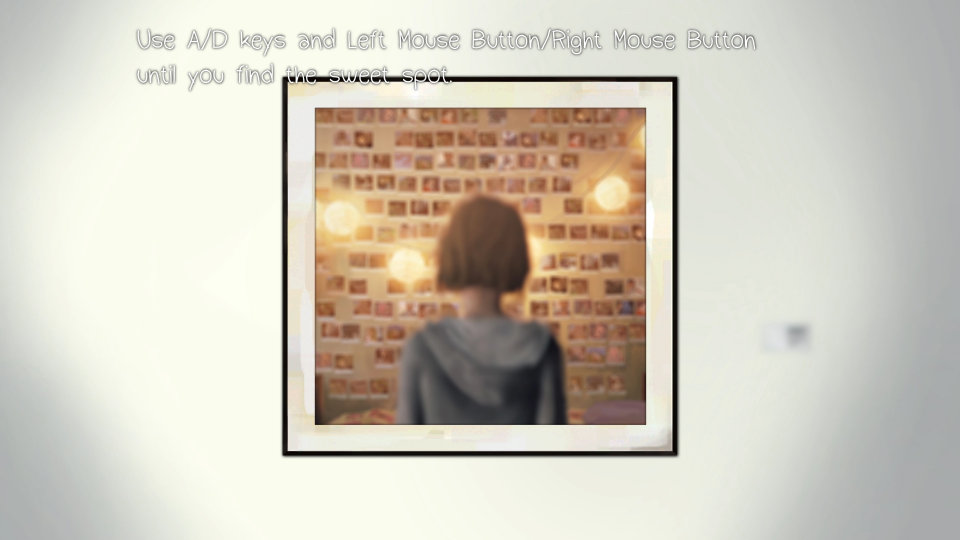

In addition to rewinding time, Max can focus on a photograph and jump back to when it was taken; these jumps are short, temporary, and more or less limited to the area framed; however, Max can still dramatically alter the timeline.

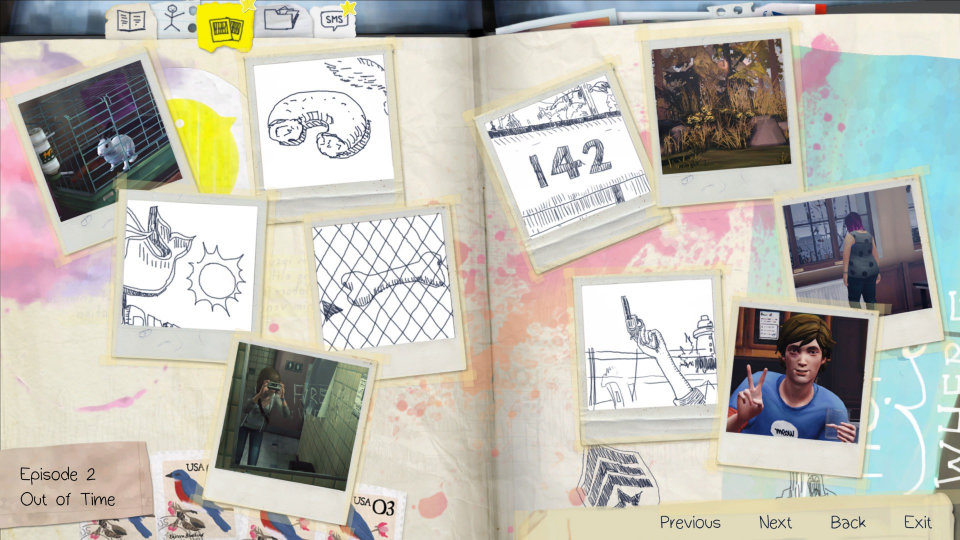

Though not necessary (and sometimes not even approapriate), Max can stop and take pictures for her album. The sketches indicate the target subjects, and the photograph replaces them when Max actually snaps the picture.

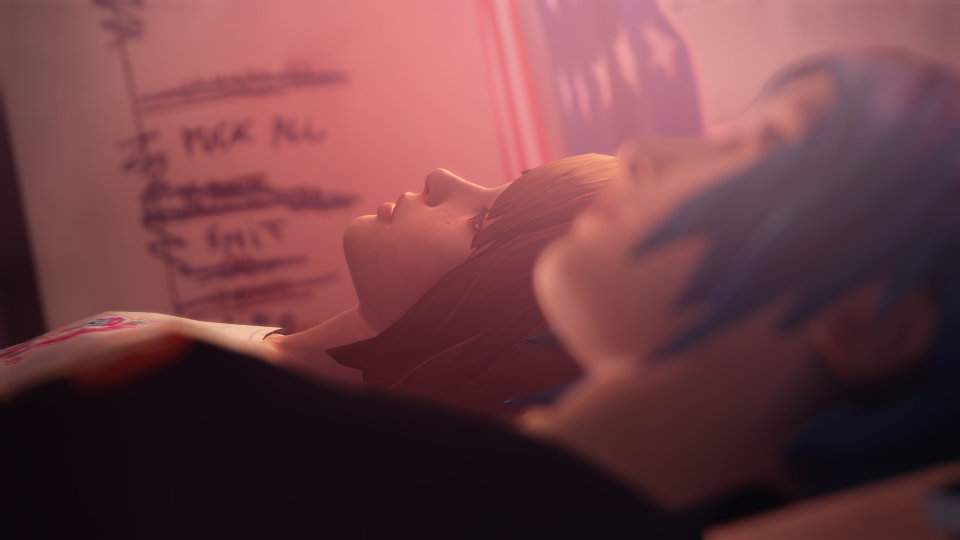

Life is Strange is rich with stylistic montages at the beginning and end of each episode. There’s also numerous places where Max can sit or lie down and think aloud while the camera drifts and wanders, switching between an array of artistic angles.

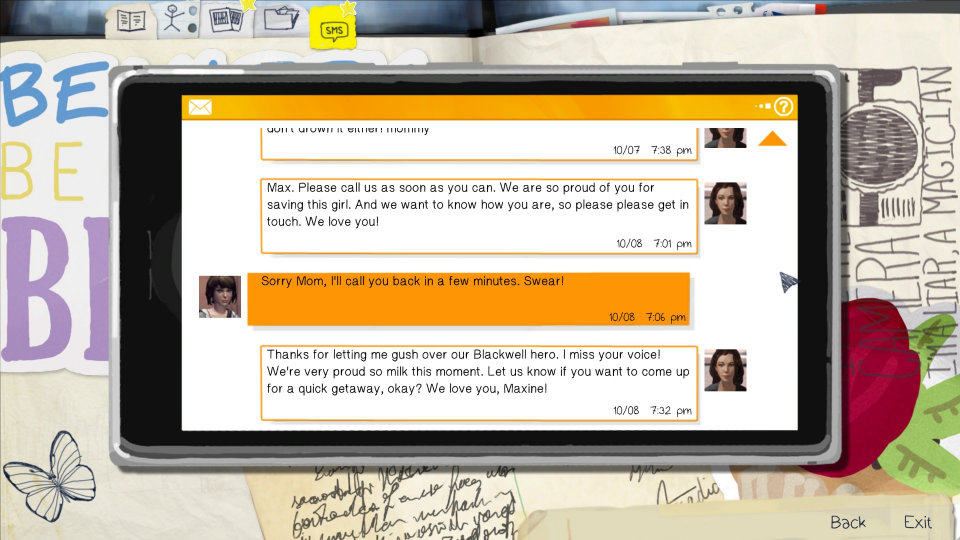

A complaint I have with dialog options in general (not just Life is Strange) is that the prompts don’t always convey tone, so your character ends up saying something meaner or nicer than you intended. But that’s where checkpoints come in handy.

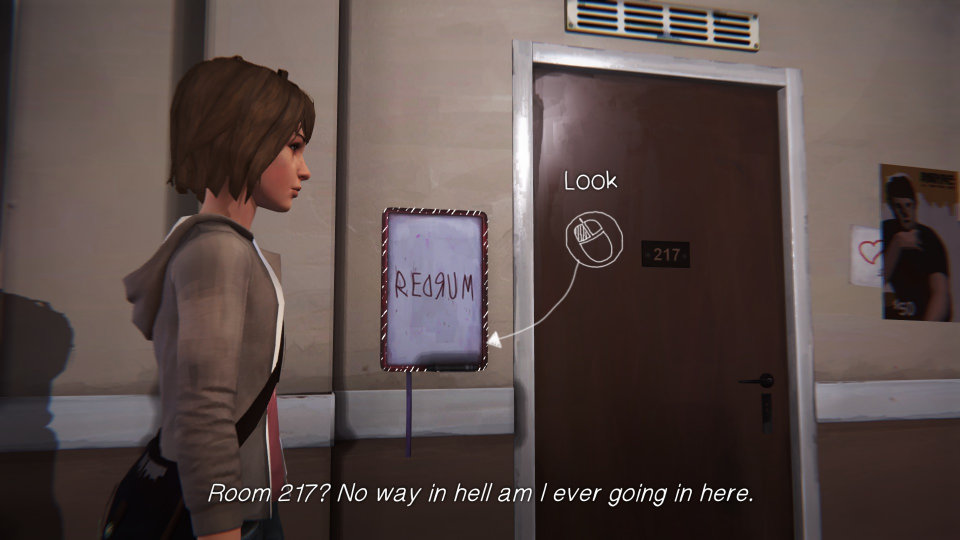

And do you remember how Max lost touch with her best friend? She inevitably runs into Chloe who, while not outright hostile, does harbor an understandable resentment—her father did pass away around the same time Max moved away—and that bitterness occasionally slips out in verbal stabs (especially if you pick dialog options that side against her). But Max never picks a fight with Chloe. She never even defends herself from Chloe’s accusations, even when they are unfair. She apologizes because she genuinely feels like she let Chloe down when her friend needed her most. More importantly: Max spends the rest of the game trying to atone for, in a sense, losing Chloe while simultaneously vowing not to lose her again. And this is what makes characters sympathetic: when they do have short comings, when they do make mistakes, and instead of brushing it off or dwelling on it endlessly, they use it to fuel their determination to never make that mistake again. At one point, after going through hell, Max finds a timeline with her own personal, perfect, happy ending, but it comes at the expense of Chloe and everyone she cares about. And without a second thought, she gives up her hopes and dreams, jumps back in time, and faces her own personal hell (again) because, God damn it, she failed her best friend once and it’s going to take more than hell for Max Caulfield to let it happen again—not while she has the power to turn back time. So when her best friend in all the world says, “I’ll always be with you,” and Max answers, “Forever.” You know she means it. And in the best storytelling traditions, Max’s greatest strength, her compassion, is also her downfall. It wouldn’t be a time-travel story without ripple effects that complicate the present and future. As the central conflict escalates, Max rises up to protect those she loves from bullies, from corrupt administrations, overzealous militants, knife-wielding criminals, elusive kidnapper, and even a powerful businessman. And the more Max bends time to her will, the more it becomes apparent that the main antagonist of Life is Strange is neither man nor his machinations, rather fate itself. The more she fights it, the more she pays in not just her health and her sanity. And not just her, fate also lashes out against the world around her. That’s what makes Max’s story so compelling and tragic. She just wants to make people happy by making their lives a little better, a little more just—for the coldhearted aggressors to get their long overdue taste of karma and for the peaceful innocents to live without fear. But she can’t fix everything. She can’t help everyone. And as hard as she tries, she can’t make life fair. That’s how her awesome power becomes a burden and a curse so much so that in the end it’s Max who needs saving, and it’s her friend—the very soul Max has fought so fiercely to protect—Chloe Price who realizes that her friend’s pure and benevolent efforts to craft a better future are tearing her—and reality—apart. It’s Chloe, herself, who pleads with Max to let go, to stop torturing herself with the burden of playing God. That everyone, even Maxine Caulfield, has only one life to live, and the answer isn’t to obsess over the past, rather, to make the most out of the present and to cherish the opportunity to make a better future with our choices here and now. While you control Max, the plot revolves around Chloe and her mission to find her missing friend, Rachel Amber. And even though Rachel essentially replaced Max in Chloe’s life, even though Max feels a bit awkward and maybe even a bit jealous, she doesn’t hesitate to bring all her new powers to bear, searching Arcadia Bay and Blackwell Academy’s darkest secrets. And I have to say, there’s a sinister joy in rummaging through cabinets, drawers, files, and paperwork—completely tearing a place apart (as much as a point and click adventure will allow anyway)—and then rewinding time to leave no trace, no fingerprints, nothing ... like Max was never there. Likewise, there’s a perverse satisfaction in questioning a suspicious character and when they let a key piece of information slip, rewinding, then confronting them with said information as if Max heard it from another source, provoking said character to explain ... and then rewinding time again so they don’t remember either conversation happened. At one point Max entertains the idea of punching a deserving jackass in the face, then using her power to escape all consequences, but she declines because she fears it would become a habit, and her power has already failed her once at the worst possible time.

One annoying aspect to Life is Strange is how it goes overboard informing you that choices have consequences, literally spelling it out in black and white text just in case freezing at critical moments with various film distortions wasn’t enough.

While you do get dialog choices, you only get a narrow range of what is in character for Max at that particular moment which brings me to my favorite dialog choice in all of video games:

“Eat Shit and Die” or “Fuck You.”

”We played hide and seek in waterfalls ...

we were younger ... we were younger ...“ — Syd Matters, Obstacles Plus, as Max probes deeper and deeper into the mystery at Blackwell Academy, she learns not all the staff and students are the cartoonish caricatures they first appear to be. The aforementioned Victory Chase has moments of second thoughts, regret, and even self-doubt; she still acts like a total bitch most of the time, but she’s not evil. Max can even persuade her do good for a change (albeit, a small, temporary good, but good none-the-less.) There’s a semblance of depth, even if the presentation is heavy handed. But that didn’t bother me because Life is Strange, with its colorful stylized graphics and low-budget puppet-like animation, presents itself more as a parable with representative archetypes versus a realistic narrative exploring fully-fleshed out, nuanced characters. And you know what? Sometimes you don’t need complicated characters. Sometimes the elegant simplicity of a single secondary trait strategically selected to run counterpoint to the character’s main personality carries a certain charm unreachable in the complexities of the real world. This allows Life is Strange to create more focused, clearly defined emotional relationships between its characters, which is precisely what this game and its choices are about. Let’s face it, the point and click adventure genre has never had much in the way of gameplay. You point at something, you click on the thing, a context menu comes up with options like “look” or “take” or “speak to” and usually you solve obscure puzzles involving items in your inventory and something in the environment. Life is Strange deviates slightly and places more emphasis on dialog choices. Most of the “puzzles” involve unlocking the best options by searching Arcadia Bay’s locales and exploring / rewinding other dialog trees—far from engaging. Thus Life is Strange—and any point and click adventure game, really—lives or dies on the player’s willingness to immerse themselves in the world, to suspend their disbelief and live in Arcadia Bay, making friends with its denizens. And I found myself so absorbed in Life is Strange that I didn’t pick the options that appealed to me personally nor did I choose the path that, mechanically speaking, was correct from a metagame perspective. For each and every choice, I asked, “What would Max do? What does Max think is right?” For example: when Max first meets up with Chloe, she can explore Chloe’s room and interact with a dozen different items, and in video games, ransacking literally everything everywhere is not just expected, but mandatory. However, poking around and violating Chloe’s privacy didn’t feel like something Max would do, so I didn’t make her. And I appreciated that Life is Strange allowed me to not do it. My choice probably did lock away arbitrary dialog options, but I didn’t care. I can live with that. It didn’t punish me with a brick wall or impossible boss fight (one perk this genre has going for it). It let me play Max the way I felt she should be played. And you know what? If I play again, I’ll make the same choices even if I know those choices are a mistake because in that moment Max has no way of knowing. That is immersion. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||