Formula is fine, but The Wizard follows its formula without conviction. It doesn’t give depth or reason to hardly any of the characters’ actions. Good guys are good guys because they’re good guys and so on.

For example: Lucas spends half the movie trying to keep the protagonists from participating in the tournament like a bad guy should, but Jimmy runs away from their one and only encounter. So why is Lucas obsessed with keeping him out of the competition?

Review by Jay Wilson I never saw The Wizard growing up, but some of my friends did and recommended it to me back during the height of Mario 3’s success. I’d often see it sitting on the shelf at the rental place but never had enough interest to actually pick it up; I’d always find another movie or perhaps even an NES game. And through the years, it seems even the most enthusiastic voices of the target audience have grown up and now echo the critical reception, calling it a wall-to-wall pandering cheese-fest. So I didn’t miss anything, right? Well, like most of my Netflix ventures these days, out of the blue I said, “Eh, what the hell?” and gave it a shot, and to my surprise, I actually liked it a lot more than I thought I was going to ... and also hated it a lot more. Yes, both. In the age of eSports, speed running, long plays, and Twitch, The Wizard is charmingly hilarious in its inaccuracy. In a scene that sets up the movie, Corey Woods puts in a quarter to an arcade machine to keep his younger half-brother, Jimmy, busy while he goes to buy a bus ticket. A brief conversation later, he pulls Jimmy away from said arcade, but not before noting, “You got fifty thousand in Double Dragon?” No, he didn’t. You really can’t do anything noteworthy in that time frame in any video game, except perhaps tool-assisted speed running with warp zones on the table (neither of which really apply to Double Dragon). I know it’s a movie, and movies always exaggerate these things for pacing purposes—which I appreciate, by the way—but it’s still funny. Just like how it’s funny that the featured gameplay from supposedly world-class experts is mediocre at best even by my proudly amateurish standards and that the parts of all the games shown are always early levels and not, just to pick a random example, “the hallway” from Castlevania. I also found the usual exaggerated controller handling amusing. Once again, I understand why: watching someone play video games is pretty boring because most of the time a gamer stares at a screen and moves his thumbs. That’s it. At a particularly challenging part, you might get entire hand movement, a funny face, a craned neck, and maybe some foot action, but those are usually isolated incidents unless, of course, you’re playing something like the turbo charged airship in Mario 3’s Dark World. There’s a scene where the father, Sam Woods, goes to sleep while his eldest son, Nick, stays up playing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Morning comes, and the game’s music continues playing, but it’s not the son playing. Nope, now it’s the father ... and his hands are all over the place, mashing the buttons as fast as possible. And having owned and extensively played the NES Ninja Turtles so much that I can still hear the music and sound effects in my sleep (Konami titles had killer soundtracks), I couldn’t help but notice, “He’s awfully animated to be playing a level in which nothing much is happening.”

This would be a great subversion of expectations; however, in the context of his child being missing, there’s absolutely no reason for Sam to bother with his son’s game system. A gag like this doesn’t need much of an explanation, but it needs something...

And don’t even get me started on this. This isn’t It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World where a bunch of greedy assholes obstruct each other from reaching a cash prize. Kids are out in the world alone. This rivalry could cost children their lives.

And it’s not that I have unrealistic expectations. I’m fine with Haley yelling winning roulette bets across a casino and taking the lion’s share of the winnings, handing Spankey (who won the money) his tiny cut like she’s an adult giving a kid his allowance.

Truth be told: I liked the kids. I liked the group’s dynamic. I liked the adventure they had. I even liked the typical awkward young boy meets young girl / not knowing what to do or say kiss scene.

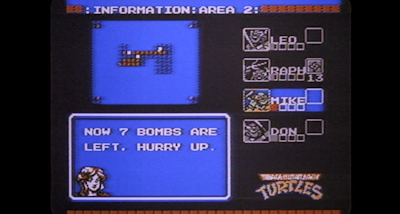

Not to mention his button presses are all wrong. You can hear the soundtrack which provides an audio roadmap for all the jumping, landing, attacking, hit detection, powerups, and player/enemy deaths because everything has an accompanying sound effect. But even without intimate familiarity with TMNT, any gamer can tell when someone is actually playing a game and when they’re pantomiming because there are few games where you mash the B-button a million times per second, and in most cases you actually spend more time waiting to push buttons than actually pushing buttons. I don’t want to say games have a pattern for their inputs, but they do have a jazz-like improvised rhythm. For example, some Beat ‘Em Ups don’t let you move and attack at the same time, so you have to stop pushing buttons entirely to get to the next area. In Platformers the height and distance of a jump is determined by how long you hold the button down and will throw a variety of short and tall platforms as well as narrow and wide pits. And Racing games have you holding one button down most of the time. It sounds like a nitpick, but this isn’t a complaint. Just a playful observation. The Wizard is not so much a movie about gaming by gamers, rather a movie about gaming by outsiders. It’s what a non-gamer would act out in charades if his scene was “playing a video game.” And that’s what I like about the movie. It’s a time capsule of the perspective all of us had to live with before video games went mainstream, and it is absolutely accurate in that regard. I bring all this up neither to tear down nor to establish any kind of gamer cred, rather to demonstrate that I’m willing to suspend my disbelief to accommodate even a blatantly wrong, not to mention far reaching premise. Every movie provides a thesis. This movie is a power fantasy written from a child’s point of view. It’s about two boys, Corey and Jimmy, who run away and eventually compete in a gaming tournament. Along the way, they hitch a ride with a motorcycle gang because to a nine year old, there’s no one cooler than a tough looking tattooed dude in leather and sunglasses on a roaring Harley Davidson. I expect no less from this movie. So what bothers me about The Wizard? It not what the runaway Woods half-brothers and their female sidekick, Haley, do, rather what the adults around them and searching for them do. In one scene, the trio decide to pool their resources, and the driver happens to glance back in time to see a couple of one dollar bills mixed in with a five and a twenty that magically add up to eighty-seven according to the dialog. The driver’s eyes go wide, he perks up, slams on the brakes, and chases the kids around, robbing them and leaving them abandoned on the side of the road. Okay, 1. If these old timey farmers are generous enough to give three helpless kids a ride back to the safety of a town, why did they rob them and dump them in the middle of nowhere to die? 2. If these people are disturbed and desperate enough to rob children for relative pocket change (yes, even in 1989), wouldn’t it have crossed their mind to go all out and kidnap them for, you know, real money? I can accept kind hearted strangers, or I can accept naughty PG13 kidnappers, but I can’t accept this goofy hybrid of sweet, innocent good Samaritans who succumbs to temptation over petty cash that might afford a full tank of gas, a couple of pizzas, and a yoyo. But I reserve my biggest complaints for the adults actively participating in the search. First as mentioned above, the father, Sam Woods, not only plays the NES in a clever (if inappropriate) little sight-gag, but gets clinically addicted to it. In the context that he and his eldest son are looking for the youngest two boys who have run away and, theoretically, are in danger of running into this world’s abundance of perverted and twisted individuals who could traumatize them for life, hooking up a game system in a hotel room—even if it is done by the eldest son—does not come across as something these characters would do. They have bigger things on their minds. In a later scene, when their truck is being fixed, the eldest son walks into frame wiping oil off his hands, presumably from helping fix said truck. And where is the father? Sitting on his ass playing a frickin’ video game. What the hell? Why is he still sitting there pouting after the son disconnects him and walks away with his “toy”? Seriously? Getting to level four is more important than your children? Maybe in another movie with another premise this role-reversal might be funny, but with missing children in the equation, I just want to punch Sam in the face and demand, “What is wrong with you?!”

Say what you want about Video Armageddon’s excessively intense and slightly creepy announcer, I thought he stole the entire third act.

At the tournament, the stated scores never match the actual scores clearly visible on screen. Although I didn’t confirm it on the initial viewing, I did suspect a discrepancy based on my knowledge of Mario 3’s scoring system.

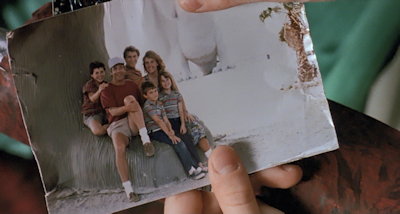

And even that pales next to the rivalry Sam develops with Putnam, the man who specializes in returning runaways. Writer David Chisholm has this character actually go up to the father and say, “I make my money by bringing kids in, and I don’t make it if someone brings the kid in first ... so let’s not be getting in my way, okay?” And for the rest of the movie, these two actively sabotage each other: Putnam slashes Sam’s tires, Sam smashes his car with a shovel, Sam rams Putnam’s car with his truck, and Putnam pays a tow truck to haul Sam’s vehicle away and strip it down. Are you fucking kidding me? I get that the filmmakers wanted a bad guy, but you can’t establish three minors travelling cross-country through a desolate wasteland and continue along, pretending they’re safe and sound in their own back yard while these jackasses spend the entire movie having a pissing contest. You have to anchor something in reality. I don’t expect this movie to go into Grave of the Fireflies territory, exploring all the soul-rending tragedy that can happen to children on their own, but I do expect the “adults” to at least acknowledge it as a possibility and grow the fuck up. What saves the movie for me, though, is Jimmy, himself. I liked the kid. I really liked his character. I sympathized with him. I wanted to know more about his autism-like condition and really wished the movie would have focused more on exploring his obsession with “California.” He carries around a lunchbox everywhere he goes, and when some bullies push him down and open it up, expecting to find cash or something valuable, all they find are pictures, baby shoes, and other memories of a twin sister who drowned. At the very end, the meaning of “California” is revealed when Jimmy gets out of the car and sprints to a tourist trap where the last family picture with Jenn, the dead sister, was taken, where everyone was happy. Jimmy leaves his lunchbox, having made peace and said his final farewell, implying that that’s what he wanted to do all along but was too shy/embarrassed or didn’t know how to express it the way an actual traumatized child would actually behave. It’s a genuinely touching moment that gives a fleeting glimpse of what the movie could have been, but I have to stress that it’s only a glimpse because the information is so mishandled that up until halfway through the movie I mistakenly thought Jenn was Jimmy’s birth mother and not his sister.

This therapy scene is the most organic place to let the audience know Jimmy watched his twin sister die right in front of him, yet it’s not stated for another forty-five minutes; meanwhile, it goes out of its way to immediately establish Corey and Jimmy as only half-brothers when there’s no plot-related reason to make them half-brothers.

Regardless, I really like what it could have been had it explored Jenn’s death and let that tragedy serve as a catalyst for Jimmy’s journey where his rival, Lucas Barton, challenges him—where Jimmy struggles, has to push himself, and ultimately overcomes; but it never gets there because it always gets distracted with contrived cinematic clichés that make no sense in the context of its story. And so at the same time, I hate The Wizard for what it actually is. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||