Spellbound was one of the first movies to seriously and directly incorporate Psychiatry into its story.

Look for the trademark cameo about 39 minutes in. Frame right, coming out of the elevator with a cigarette and violin case.

Notice how the discarded coat (just left of Ingrid Bergman) is arranged in the frame to create symmetry. This is the attention to detail which made Hitchcock so great.

... explicit lines from the room's features, implied lines from the figures' eye contact ... you could literally teach an art class with this frame.

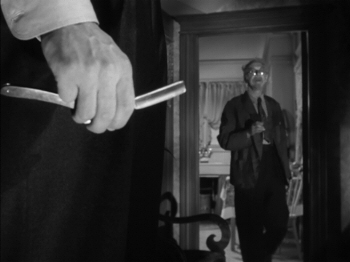

Check out how in a single frame, Hitchcock captures the menace of a killer and his victim.

Even if you think this POV shot of a man drinking from a glass is silly, you have to admire Hitchcock's willingness to experiment.

Review by Jay Wilson I remember a few years back, I watched a series of interviews with the great Chuck Jones (director and animator of many beloved Looney Tunes classic cartoons.) And in this interview, Mr. Jones sat down with a pencil and a stack of papers, and he narrated the history of animated cartoons while drawing the characters from his and other studios of the day. And while he spoke, he drew ... and while he drew, I watched in awe at the precision, at the confidence, the economy, and speed in which he could make his medium yield the characters of Mickey, Bugs, and Daffy—brought to life effortlessly on the page in the span of a few short seconds, created with only a handful of pencil strokes. Finished with that page, Mr. Jones tossed the paper over his shoulder and went to work on the next sheet and never once did he pause in his narration. I was watching a master who intimately knew his craft, who commanded every aspect of his medium, and who loved what he did. Watching Sir Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound, I had that exact same feeling of watching an artist in complete control, dancing with his medium. Take for example, the magnificent shot of a mentally disturbed Gregory Peck descending a winding stairway with razor blade in hand. With the camera positioned at the bottom of the stairs, aimed up, the frame is alive with diagonal lines from the banister and ceiling as it follows Peck, moving through slits of light and ominous shadow. When he reaches the bottom of the stairs, his hand, holding the razor, fills the entire frame. Without a single cut, the focal points seamlessly evolve in front of our very eyes from a medium shot to an extreme close up. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Spellbound, like so many other Hitchcock tales, is the story of a protagonist on the run who must figure his way out of the circumstance that has ensnared him. What I like about this particular iteration, however, is the prominence of the Ingrid Bergman character and the twist she adds to the formula. Bergman plays a bookish psychiatrist named Constance Petersen working at a home for the psychologically disturbed, forever batting away the subtle (and not-so-subtle) flirtations of her coworkers. With the head Doctor departing, a new world-renown psychiatrist, Dr Anthony Edwards (Gregory Peck), is coming in to fill his shoes. Petersen and Edwards are smitten with one another not unlike a typical 40s romance picture; however, it’s not long before strange behavioral quirks start manifesting in the new doctor, and not long before they figure out this man is not Edwards. The real Dr. Edwards went missing days ago, and the imposter is an amnesiac who, authorities believe, is the last person who saw the real Dr. Edwards alive. The imposter (who can’t even remember his own name) flees the night before discovery, but Dr. Petersen vows to help him recover his memories and prove his innocence even while they both evade the police. It’s a unique reversal in that the female lead holds the reigns and drives the story, while the male protagonist spends much of his screen time in a fragile emotional and psychological state, often fainting, or staring wide-eyed at black stripes on a white surface which mysteriously sets him off. With Constance in the driver’s seat, this leads to one of my favorite scenes where she knows the faux Dr. Edwards is staying in a hotel, but doesn’t know what room. She makes camp in the lobby to wait where, not surprisingly, some poor shmuck wanders over and starts hitting on her (who wouldn’t hit on Ingrid Bergman?). He’s driven off by the “House Detective” who is tasked with stopping trouble before it starts. “I’m trained to read people. Ya know, like one of them Psychologists,” he explains, believing her to be some poor school teacher and frazzled wife, “I’ve been watching you. You’re looking for someone. It’s your husband, isn’t it? Had a fight didn’t you? Need to make up?” To which Bergman gives a coy and impish sideways smile as she goes along, “yeah. I need to find him.” And watch the sparkle in her eyes as she plays off the helpless damsel stereotype to manipulates this poor man into giving her the information she needs. Hitchcock may be most famous as “the master of suspense”, but fans of maestro know, he was pretty darn good at comedy too. As authorities close in, Dr. Petersen and her patient seek refuge with her mentor, Dr. Alexander Brulov (Michael Chekhov). In a movie about doctors, it seems almost obligatory to have an old white haired, balding man who stares through a thick set of spectacles and speaks with a foreign accent, but somehow despite the clichés Chekhov delivers one of the most charming performances of the movie (although for the life of me I’m not sure if I can articulate how or why.) When Dr. Petersen formulates a lie to explain their sudden unexpected presence in his home—that they got married recently—Dr Brulov cheerfully states, “How wonderful! I always say: women make the best psychiatrists until they fall in love. Then they make the best patients.” And somehow the remark rings with more fatherly affection than condescension or sexism. “He doesn’t seem to mind that we don’t have bags even though we’re supposedly just married.” Our amnesiac protagonist observes. “Oh no,” Constance answers, “he wouldn’t notice something like that.” And only a few short scenes later, she stands before her mentor a little embarrassed after her scheme escalated beyond her control, and Brulov scolds her, “you think I can’t see two plus two is four?” again, not unlike a father dealing with a teenage child who got themselves in trouble and then tried to lie their way out. And, again, there’s something enduring about how Brulov embodies both authority and affection.

Salvadore Dali famously contributed and influenced Spellbound's dream sequence; although, the original vision never made it to the screen.

Fatherly figure, Dr. Brulov (Chekhov) hovers over an amnesiac (Peck) while his pupil (Bergman) assists. And just look at the rhythm created by that triangular cluster of faces and notice how powerful a focal point it creates.

To today’s audiences, many films of this era feature awkward climaxes due to the limitations of the technology at the time. Spellbound is no exception, using obvious rear-screen projection and miniatures to simulate ... well, that’s part of the mystery of the plot. Like many early films with rear-screen projection, it’s clear the characters do not occupy the same space as the background. Despite the near-self-parody silliness of the sequence, I found myself admiring Hitchcock for trying, unafraid to take risks and push technology as far as it could go ... and I couldn’t be more impressed that the film, as a whole, still works despite that sequence’s failure. But I suspect the main reason the rear-screen projection sequence doesn’t work and the reason why the film as a whole still stands strong is because Hitchcock delivers such a flawless frame for the rest of the film. Watch Spellbound. Just watch it. You can see Hitchcock’s past in silent films where the frame, itself, had to state everything visually. The phone rings, and Hitch cuts to a close up of the phone. The camera pulls back revealing four figures sitting anxiously in the background. And now, not only does the audience have a wonderful symmetrical frame to look at, but this aesthetically balanced picture serves a functional purpose as well: now we know where the phone is in relationship to the room and the characters. Later when Doctor Brulov returns and addresses his company, two detectives wishing to speak with him about the disappearance of Dr Edwards, watch Ingrid Bergman slither through the background, pausing to give uneasy glances at them, knowing how close she and the faux-Edwards are to being caught. But go back and watch that scene a second time, and notice how Brulov’s character takes on a different dimension once you know everything. It’s no accident that he keeps the detectives with their backs to Bergman. Hell, even for something as simple as the new ‘Doctor’ shaking hands with his new coworkers, notice how Hitchcock positions his actors (of various sizes), how he uses the architecture of the room, and how he uses the furniture to create a balanced image. And once you know all the secrets of Spellbound, watch it again, and notice how he groups his characters together. There’s more to the Hitchcock frame than aesthetics. One could quite literally take a screen capture from nearly any scene in Spellbound, frame it, and have a nice picture to hang on the wall. And, more importantly, have a nice picture that means something. | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||